| 送交者: Leon21[♂★品衔R5★♂] 于 2021-01-22 10:36 已读 914 次 | Leon21的个人频道 |

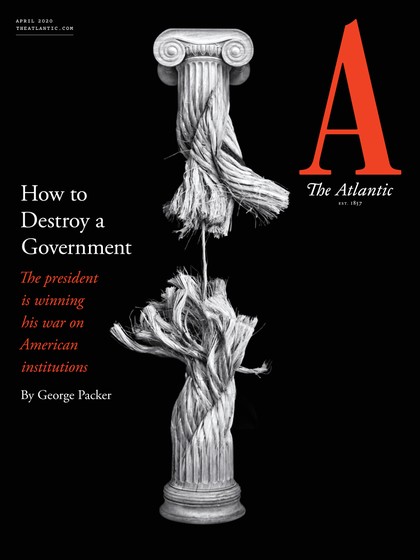

大西洋月刊2020年四月刊文 6park.comThe President Is Winning His War on American InstitutionsHow Trump is destroying the civil service and bending the government to his will 6park.com

Photo rendering by Patrick White Story by George Packer APRIL 2020 ISSUE 6park.comPOLITICS 6park.com 6park.com

When donald trump came into office, there was a sense that he would be outmatched by the vast government he had just inherited.

The new president was impetuous, bottomlessly ignorant, almost chemically inattentive, while the bureaucrats were seasoned, shrewd, protective of themselves and their institutions. They knew where the levers of power lay and how to use them or prevent the president from doing so. Trump’s White House was chaotic and vicious, unlike anything in American history, but it didn’t really matter as long as “the adults” were there to wait out the president’s impulses and deflect his worst ideas and discreetly pocket destructive orders lying around on his desk.

After three years, the adults have all left the room—saying just about nothing on their way out to alert the country to the peril—while Trump is still there.

[iframe]"[/iframe]To hear more feature stories, get the Audm iPhone app. 6park.com

James Baker, the former general counsel of the FBI, and a target of Trump’s rage against the state, acknowledges that many government officials, not excluding himself, went into the administration convinced “that they are either smarter than the president, or that they can hold their own against the president, or that they can protect the institution against the president because they understand the rules and regulations and how it’s supposed to work, and that they will be able to defend the institution that they love or served in previously against what they perceive to be, I will say neutrally, the inappropriate actions of the president. And I think they are fooling themselves. They’re fooling themselves. He’s light-years ahead of them.”

The adults were too sophisticated to see Trump’s special political talents—his instinct for every adversary’s weakness, his fanatical devotion to himself, his knack for imposing his will, his sheer staying power. They also failed to appreciate the advanced decay of the Republican Party, which by 2016 was far gone in a nihilistic pursuit of power at all costs. They didn’t grasp the readiness of large numbers of Americans to accept, even relish, Trump’s contempt for democratic norms and basic decency. It took the arrival of such a leader to reveal how many things that had always seemed engraved in monumental stone turned out to depend on those flimsy norms, and how much the norms depended on public opinion. Their vanishing exposed the real power of the presidency. Legal precedent could be deleted with a keystroke; law enforcement’s independence from the White House was optional; the separation of powers turned out to be a gentleman’s agreement; transparent lies were more potent than solid facts. None of this was clear to the political class until Trump became president. 6park.com

But the adults’ greatest miscalculation was to overestimate themselves—particularly in believing that other Americans saw them as selfless public servants, their stature derived from a high-minded commitment to the good of the nation.

From October 2018: Anne Applebaum on polarization and the eternal appeal of authoritarianism

When Trump came to power, he believed that the regime was his, property he’d rightfully acquired, and that the 2 million civilians working under him, most of them in obscurity, owed him their total loyalty. He harbored a deep suspicion that some of them were plotting in secret to destroy him. He had to bring them to heel before he could be secure in his power. This wouldn’t be easy—the permanent government had defied other leaders and outlasted them. In his inexperience and rashness—the very qualities his supporters loved—he made early mistakes. He placed unreliable or inept commissars in charge of the bureaucracy, and it kept running on its own.

But a simple intuition had propelled Trump throughout his life: Human beings are weak. They have their illusions, appetites, vanities, fears. They can be cowed, corrupted, or crushed. A government is composed of human beings. This was the flaw in the brilliant design of the Framers, and Trump learned how to exploit it. The wreckage began to pile up. He needed only a few years to warp his administration into a tool for his own benefit. If he’s given a few more years, the damage to American democracy will be irreversible. 6park.com

This is the story of how a great republic went soft in the middle, lost the integrity of its guts and fell in on itself—told through government officials whose names under any other president would have remained unknown, who wanted no fame, and who faced existential questions when Trump set out to break them.

Photo rendering by Patrick White

1. “We’re Not Nazis”

Erica Newland went to work at the Department of Justice in the last summer of the Obama administration. She was 29 and arrived with the highest blessings of the meritocracy—a degree from Yale Law School and a clerkship with Judge Merrick Garland of the D.C. Court of Appeals, whom President Obama had recently nominated to the Supreme Court (and who would never get a Senate hearing). Newland became an attorney-adviser in the Office of Legal Counsel, the department’s brain trust, where legal questions about presidential actions go to be answered, usually in the president’s favor. The office had approved the most extreme wartime powers under George W. Bush, including torture, before rescinding some of them. Newland was a civil libertarian and a skeptic of broad presidential power. Her hiring showed that the Obama Justice Department welcomed heterodox views.

The election in November changed her, freed her, in a way that she understood only much later. If Hillary Clinton had won, Newland likely would have continued as an ambitious, risk-averse government lawyer on a fast track. She would have felt pressure not to antagonize her new bosses, because elite Washington lawyers keep revolving through one another’s lives—these people would be the custodians of her future, and she wanted to rise within the federal government. But after the election she realized that her new bosses were not likely to be patrons of her career. They might even see her as an enemy. Among career officials, fear set in. They saw what was happening to colleagues in the FBI who had crossed the president.

She decided to serve under Trump. She liked her work and her colleagues, the 20 or so career lawyers in the office, who treated one another with kindness and respect. Like all federal employees, she had taken an oath to support the Constitution, not the president, and to discharge her office “well and faithfully.” Those patriotic duties implied certain values, and they were what kept her from leaving. In her mind, they didn’t make her a conspirator of the “deep state.” She wouldn’t try to block the president’s policies—only hold them to a high standard of fact and law. She doubted that any replacement would do the same. 6park.com

Days after Trump’s inauguration, Newland’s new boss, Curtis Gannon, the acting head of the Office of Legal Counsel, gave a seal of approval to the president’s ban, bigoted if not illegal, on travelers from seven majority-Muslim countries. At least one lawyer in the office went out to Dulles Airport that weekend to protest it. Another spent a day crying behind a closed office door. Others reasoned that it wasn’t the role of government lawyers to judge the president’s motives.

From June 2018: Jeff Sessions is killing civil rights

Employees of the executive branch work for the president, and a central requirement of their jobs is to carry out the president’s policies. If they can’t do so in good conscience, then they should leave. At the same time, there’s good reason not to leave over the results of an election. A civil service that rotates with the party in power would be a reversion to the 19th-century spoils system, whose notorious corruption led to the 1883 Pendleton Act, which created the modern merit-based, politically insulated civil service.

In Trump’s first year an exodus from the Justice Department began, including some of Newland’s colleagues. Some left in the honest belief that they could no longer represent their client, whose impulsive tweets on matters such as banning transgender people from the military became the office’s business to justify, but they largely kept their reasons to themselves. Almost every consideration—future job prospects, relations with former colleagues, career officials’ long conditioning in anonymity—goes against a righteous exit. 6park.com

Newland didn’t work on the travel ban. Perhaps this distance allowed her to hold on to the idea that she could still achieve some good if she stayed inside. Her obligation was to the country, the Constitution. She felt she was fighting to preserve the credibility of the Justice Department. That first year, she saw her memos and arguments change outcomes.

Things got worse in the second year. It seemed as if more than half of the Office of Legal Counsel’s work involved limiting the rights of noncitizens. The atmosphere of open discussion dissipated. The political appointees at the top, some of whom had voiced skepticism early on about the legality of certain policies, were readier to make excuses for Trump, to give his fabrications the benefit of the doubt. Among career officials, fear set in. They saw what was happening to colleagues in the FBI who had crossed the president during the investigation into Russian election interference—careers and reputations in ruins. For those with security clearances, speaking up, or even offering a snarky eye roll, felt particularly risky, because the bar for withdrawing a clearance was low. Steven Engel, appointed to lead the office, was a Trump loyalist who made decisions without much consultation. Newland’s colleagues found less and less reason to advance arguments that they knew would be rejected. People began to shut up. 6park.com

After Erica Newland concluded that her work in the Justice Department involved saving Trump from his own lies, she resigned. Photographed at home in Maryland, February 11, 2020. (Peyton Fulford)One day in May 2018, Newland went into the lunchroom carrying a printout of a White House press release titled “What You Need to Know About the Violent Animals of MS-13.” At a meeting about Central American gangs a few days earlier, Trump had used the word animals to describe undocumented immigrants, and in the face of criticism the White House was digging in. Animals appeared 10 times in the short statement. Newland wanted to know what her colleagues thought about it. 6park.com

Eight or so lawyers were sitting around a table. They were all career people—the politicals hadn’t come to lunch yet. Newland handed the printout to one of them, who handed it right back, as if he didn’t want to be seen with it. She put the paper faceup on the table, and another lawyer turned it over, as if to protect Newland: “That way, if Steve walks in …”

Newland turned it over again. “It’s a White House press release and I’m happy to explain why it bothers me.” The conversation quickly became awkward, and then muted. Colleagues who had shared Newland’s dismay in private now remained silent. It was the last time she joined them in the lunchroom.

No one risked getting fired. No one would become the target of a Trump tweet. The danger might be a mediocre performance review or a poor reference. “There was no sense that there was anything to be gained by standing up within the office,” Newland told me recently. “The people who might celebrate that were not there to see it. You wouldn’t be able to talk about it. And if you’re going to piss everyone off within the department, you’re not going to be able to get out” and find a good job.

She hated going to work. In the lobby of the Justice Department building, six blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House, Newland had to pass under a large portrait of the president. Every morning as she entered the building, she avoided looking at Trump, or she used side doors, where she wouldn’t be confronted with his face. At night she slept poorly, plagued by regrets. Should she have pushed harder on a legal issue? Should she engage her colleagues in the lunchroom again? How could she live with the cruelty and bigotry of executive orders and other proposals, even legal ones, that crossed her desk? She was angry and miserable, and her friends told her to leave. She continued to find reasons to stay: worries about who would replace her, a determination not to abandon ship during an emergency, a sense of patriotism. Through most of 2018 she deluded herself that she could still achieve something by staying in the job. 6park.com

In 1968, James C. Thomson, a former Asia expert in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, published an essay in this magazine called “How Could Vietnam Happen? An Autopsy.” Among the reasons Thomson gave for the war was “the ‘effectiveness’ trap”—the belief among officials that it’s usually wisest to accept the status quo. “The inclination to remain silent or to acquiesce in the presence of the great men—to live to fight another day, to give on this issue so that you can be ‘effective’ on later issues—is overwhelming,” he wrote. The trap is seductive, because it carries an impression of principled tough-mindedness, not cowardice. Remaining “effective” also becomes a reason never to quit.

as the executive orders and other requests for the office’s approval piled up, many of them of dubious legality, one of Newland’s supervisors took to saying, “We’re just following orders.” He said it without irony, as a way of reminding everyone, “We work for the president.” He said it once to Newland, and when she gave him a look he added, “I know that’s what the Nazis said, but we’re not Nazis.”

“The president has said that some of them are very fine people,” Newland reminded him.

“Attorney General Sessions never said that,” the supervisor replied. “Steve never said that, and I’ve never said that. We’re not Nazis.” That she could still have such an exchange with a supervisor seemed in itself like a reason not to leave. 6park.com

But Newland, who is Jewish, sometimes asked herself: If she and her colleagues had been government lawyers in Germany in the 1930s, what kind of bureaucrat would each of them have been? There were the ideologues, the true believers, like one Clarence Thomas protégé. There were the opportunists who went along to get ahead. There were a handful of quiet dissenters. But many in the office just tried to survive by keeping their heads down. “I guess I know what kind I would have been,” Newland told me. “I would have stayed in the Nazi administration initially and then fled.” She thinks she would have been the kind of official who pushed for carve-outs in the Nuremberg Race Laws, preserving citizenship rights for Germans with only partial Jewish ancestry. She would have felt that this was better than nothing—that it justified having worked in the regime at the beginning.

newland and her colleagues were saving Trump from his own lies. They were using their legal skills to launder his false statements and jury-rig arguments so that presidential orders would pass constitutional muster. When she read that producers of The Apprentice had had to edit episodes in order to make Trump’s decisions seem coherent, she realized that the attorneys in the Office of Legal Counsel were doing something similar. Loyalty to the president was equated with legality. “There was hardly any respect for the other departments of government—not for the lower courts, not for Congress, and certainly not for the bureaucracy, for professionalism, for facts or the truth,” she told me. “Corruption is the right word for this. It doesn’t have to be pay-to-play to be corrupt. It’s a departure from the oath.” 6park.com

In the fall of 2018, Newland learned that she and five colleagues would receive the Attorney General’s Distinguished Service Award for their work on executive orders in 2017. The news made her sick to her stomach; her office probably thought she would feel honored by the award. She marveled at how the administration’s conduct had been normalized. But she also suspected that department higher-ups were using the career people to justify policies such as the travel ban—at least, the award would be seen that way. Newland and another lawyer stayed away from the ceremony where the awards were presented, on October 24.

RELATED STORIES

How America EndsJames Mattis Couldn't Take It AnymoreTop Military Officers Unload on Trump On October 27, an anti-Semitic extremist killed 11 people at a synagogue in Pittsburgh. Before the shooting, he berated Jews online for enabling “invaders” to enter the United States from Mexico. That same week, the Office of Legal Counsel was working on an order that, in response to the “threat” posed by a large caravan of Central Americans making its way north through Mexico, temporarily refused all asylum claims at the southern border. Newland, who could imagine being shot in a synagogue, felt that her office’s work was sanctioning rhetoric that had inspired a mass killer.

Adam Serwer: Trump’s caravan hysteria sparked a massacre

She tendered her resignation three days later. By Thanksgiving she was gone. In the new year she began working at a nonprofit called Protect Democracy. 6park.com

The asylum ban was the last public act of Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Trump fired him immediately after the midterm elections. Newland felt that Sessions—who had recused himself from the Russia investigation because he had spoken with Russian officials as an adviser in the Trump campaign—cared about protecting some democratic rights, but only for white Americans. He was eventually replaced by William Barr, a former attorney general with a reputation for intellect and competence. But Barr quickly made Sessions seem like a paragon of integrity. After watching him run her former department for a year, Newland wondered why she had stayed inside at all.

2. Cashing In

There’s always been corruption in Washington, and everywhere that power can be found, but it became institutionalized starting in the late 1970s and early ’80s, with the rise of the lobbying industry. The corruption that overtook the capital during that time was pecuniary and mostly legal, a matter of norm-breaking—of people’s willingness to do what wasn’t done. Robert Kaiser, a former Washington Post editor and the author of the 2010 book So Damn Much Money: The Triumph of Lobbying and the Corrosion of American Government, locates an early warning sign in Gerald Ford’s readiness to “sign up for every nasty piece of work that everybody offered him to cash in on being an ex-president.” Cashing in—once known as selling out—became a common path out of government, and then back in and out again. “There was a taboo structure,” Kaiser told me. “You don’t go from a senior Justice Department position to a senior partner in Lloyd Cutler’s law firm and then go back. It was a one-way trip. That taboo is no more.” 6park.com

From May 2005: Stuart Taylor Jr. on Lloyd Cutler, the last superlawyer

Former members of Congress and their aides cashed in as lobbyists. Retired military officers cashed in with defense contractors. Justice Department officials cashed in at high-paying law firms. Former diplomats cashed in by representing foreign interests as lobbyists or public-relations strategists. A few years high up in the Justice Department could translate into tens of millions of dollars in the private sector. Obscure aides on Capitol Hill became millionaires. Trent Lott abandoned his Senate seat early in order to get ahead of new restrictions on how soon he could start his career as a lobbyist. Ex-presidents gave six-figure speeches and signed eight-figure book deals. Trump believed he had to crush the bureaucracy or else it would destroy him.

As partisanship turned rabid, making money remained the one thing that Democrats and Republicans could still do together. Washington became a city of expensive restaurants, where bright young people entered government to do some good and then get rich. Luke Albee, a former chief of staff for two Democratic senators, learned to avoid hiring aides he would lose too quickly. “I looked out for who’s going to come in and spin out after 18 months, to renew and refresh their contacts in order to increase their retainers,” he told me. The revolving door didn’t necessarily induce individual officeholders to betray their oath—they might be scrupulously faithful public servants between turns at the trough. But, on a deeper level, the money aligned government with plutocracy. It also made the public indiscriminately cynical. And as the public’s trust in institutions plunged, the status of bureaucrats fell with it. 6park.com

The swamp had been pooling between the Potomac and the Anacostia for three or four decades when Trump arrived in Washington, vowing to drain it. The slogan became one of his most potent. Fred Wertheimer, the president of the nonprofit Democracy 21 and an activist for good government since the Nixon presidency, says of Trump: “He was ahead of a lot of national politicians when he saw that the country sees Washington as rigged against them, as corrupted by money, as a lobbyist’s game—which is a game he played his whole life, until he ran against it. People wanted someone to take this on.” By then the federal government’s immune system had been badly compromised. Trump, in the name of a radical cure, set out to spread a devastating infection.

Read: Franklin Foer on how kleptocracy came to America

To Trump and his supporters, the swamp was full of scheming conspirators in drab D.C. office wear, coup plotters hidden in plain sight at desks, in lunchrooms, and on jogging paths around the federal capital: the deep state. A former Republican congressional aide named Mike Lofgren had introduced the phrase into the political bloodstream with an essay in 2014 and a book two years later. Lofgren meant the nexus of corporations, banks, and defense contractors that had gained so much financial and political control—sources of Washington’s corruption. But conservatives at Breitbart News, Fox News, and elsewhere began applying the term to career officials in law-enforcement and intelligence agencies, whom they accused of being Democratic partisans in cahoots with the liberal media first to prevent and then to undo Trump’s election. Like fake news and corruption, Trump reverse-engineered deep state into a weapon against his enemies, real or perceived. 6park.com

The moment Trump entered the White House, he embarked on a colossal struggle with his own bureaucracy. He had to crush it or else it would destroy him. His aggrieved and predatory cortex impelled him to look for an official to hang out in public as a warning for others who might think of crossing him. Trump found one who had been nameless and faceless throughout his career.

3. “How Is Your Wife?”

Andrew McCabe joined the FBI in 1996, when he was 28, a year younger than Erica Newland was when she entered government service. He was the son of a corporate executive, a product of the suburbs, a Duke graduate, a lawyer at a small New Jersey firm. The bureau attracted him because of the human drama that investigations uncovered, the stories elicited from people who had crossed the line between the safe and predictable life of McCabe’s upbringing and the shadow world beyond the law. His wife, Jill, who was training in pediatric medicine, encouraged him to apply. He took a 50 percent salary cut to join the bureau. At Quantico, it was almost a pleasure for him to be subsumed into the uniform and discipline and selflessness of an agent’s training.

McCabe specialized in Russian organized crime and then terrorism. He rose swiftly through the ranks of the bureau and stayed out of the public eye. He had a reputation for intellect and unflappability, a natural manager. In early 2016—by then McCabe was in his late 40s, trim from triathlon competitions, his short hair going gray, the frames of his glasses black above and clear below—James Comey promoted him from head of the Washington field office to deputy director, the highest career position in the bureau, responsible for overseeing its day-to-day operations. In ordinary times the FBI’s No. 2 remains invisible to the public, but McCabe’s new job gave him a role in overseeing the investigation of Hillary Clinton’s private email server, just as the 2016 presidential race was entering its consequential phase. By summer the FBI would be digging into Trump’s campaign as well. 6park.com

In July, Comey decided to announce the closing of the email case, calling Clinton’s conduct “extremely careless” but not criminal. McCabe supported this extraordinary departure from normal procedure (the FBI doesn’t comment on investigations, especially ones that don’t result in prosecution) because the Clinton email case, played out on the front pages in the middle of the campaign, was anything but normal. Comey was a master at conveying ethical rectitude—he would rise above the din to his commanding height and convince the American people that the investigation had been righteous.

But Comey’s statement created fury on both the left and the right and badly damaged the FBI’s credibility. McCabe came to regret Comey’s decision and his own role in it. “We believed that the American people believed in us,” McCabe later wrote. “The FBI is not political.” But he should have known. He had worked on the wildly overblown Benghazi case in the aftermath of the killing of the U.S. ambassador to Libya in 2012, which “revealed the surreal extremes to which craven political posturing had gone,” and led to the equally overblown email case.

When Andrew McCabe, the deputy director of the FBI, found himself in the president’s crosshairs, his world turned upside down. Photographed in Washington, D.C., February 10, 2020. (Peyton Fulford) Having spent two decades as an upstanding G-man in a hierarchical institution, McCabe didn’t understand what the country had become. He was unarmed and unready for what was about to happen. 6park.com

Jill McCabe, a pediatric emergency-room doctor, had run for a seat in the Virginia Senate as a Democrat in 2015 in order to work for Medicaid expansion for poor patients. She lost the race. On October 23, 2016, two weeks before the presidential election, The Wall Street Journal revealed that her campaign had received almost $700,000 from the Virginia Democratic Party and the political-action fund of Governor Terry McAuliffe, a Clinton friend who had encouraged her to run. “Clinton Ally Aided Campaign of FBI Official’s Wife,” read the headline, with more innuendo than substance. McCabe had properly insulated himself from the campaign and knew nothing about the donations. FBI ethics people had cleared him to oversee the Clinton investigation, which he didn’t start doing until months after Jill’s race had ended. One had nothing to do with the other. But Trump tweeted about the Journal story, and on October 24 he enraged a crowd in St. Augustine, Florida, with the made-up news that Clinton had corrupted the bureau and bought her way out of jail through “the spouse—the wife—of the top FBI official who helped oversee the investigation into Mrs. Clinton’s illegal email server.” He snarled and narrowed his eyes, he tightened his lips and shook his head, he walked away from the microphone in disgust, and the crowd shrieked its hatred for Clinton and the rigged system.

This was the first time Trump referred to the McCabes. He didn’t use their names, but the scene was chilling. 6park.com

Within a few days, The Wall Street Journal was preparing to run a second story with damaging information about the FBI and McCabe—this time, that he had told agents to “stand down” in a secret investigation of the Clinton Foundation. The sources appeared to be senior agents in the FBI’s New York field office, where anti-Clinton sentiment was expressed openly. But the story was wrong: McCabe had wanted to continue the investigation and had simply been following Justice Department policy to keep agents from taking any overt steps, such as issuing subpoenas, that might influence an upcoming election. For the second time in a week, his integrity—the lifeblood of an official in his position—was unjustly maligned in highly public fashion. He authorized his counsel, Lisa Page, and the chief FBI spokesperson, Michael Kortan, to correct the story by disclosing to the reporter a conversation between McCabe and a Justice Department official—an authorization he believed to be appropriate, because it was in the FBI’s interest as well as his own.

The leak inadvertently confirmed the existence of an investigation into the Clinton Foundation, and it upset Comey. The director was already unhappy with the revelations about Jill McCabe’s campaign. He prepared to order McCabe to recuse himself from the Clinton email investigation, which the FBI reopened on October 28, 11 days before the election. Comey later claimed that when he’d asked McCabe about the leak, McCabe had said something like “I don’t know how this shit gets in the media.” (McCabe later said that he’d told Comey he had authorized the leak.) 6park.com

This incident, so slight amid the large dramas of those months, set in motion a series of fateful events for McCabe.

When Trump won, the McCabes thought that the new president might drop the conspiracy theory about Jill’s campaign and stop his attacks on them. “He got what he wanted,” she told me recently, “so maybe he’ll just leave us alone now. For, like, a moment I thought that.”

As Trump prepared to take power, the Russia investigation closed in on people around him, beginning with Michael Flynn, his choice for national security adviser, who lied to FBI agents about phone calls with the Russian ambassador. Trump made it clear that he expected the FBI to drop the Flynn case and shield the White House from the tightening circle of investigation. At a White House dinner for two, the new president told his FBI director that he wanted loyalty. Comey replied with a promise of honesty. Trump then asked if McCabe “has a problem with me. I was pretty rough on him and his wife during the campaign.” Comey called McCabe “a true professional,” adding: “FBI people, whatever their personal views, they strip them away when they step into their bureau roles.”

But Trump didn’t want true professionals. Either you were loyal or you were not, and draining the swamp turned out to mean getting rid of those who were not. His understanding of human motivation told him that, after his “pretty rough” treatment, McCabe couldn’t possibly be loyal—he would want revenge, and he would get it through an investigation. In subsequent conversations with Comey, Trump kept returning to “the McCabe thing,” as if fixated on the thought that he had created an enemy in his own FBI. 6park.com

“We knew that we were doomed,” Jill McCabe told me. “Our days were numbered. It was gradual, but by May we knew it could end really terribly.”

On May 9, 2017, McCabe was summoned across the street to the office of Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who informed him that Trump had just fired Comey. McCabe was now acting director of the FBI.

FROM OUR APRIL 2020 ISSUE

Subscribe to The Atlantic and support 160 years of independent journalism Subscribe

Trump wanted to see him that evening. Comey had told McCabe about Trump’s demands for loyalty, his attempts to interfere with the Russia investigation, and his suspicion of McCabe himself. McCabe fully expected to be fired any day. When he was ushered into the Oval Office, he found the president seated behind his imposing desk, with his top advisers—the vice president, the chief of staff, the White House counsel—perched submissively before him in a row of small wooden chairs, where McCabe joined them. Trump asked McCabe whether he disagreed with Comey’s decision to close the Clinton email case in July. No, McCabe said; he and Comey had worked together closely. Trump kept pushing: Was it true that people at the FBI were unhappy about the decision, unhappy with Comey’s leadership? McCabe said that some agents disagreed with Comey’s handling of the Clinton case, but that he had generally been popular.

“Your only problem is that one mistake you made,” McCabe later recalled Trump saying. “That thing with your wife. That one mistake.” McCabe said nothing, and Trump went on: “That was the only problem with you. I was very hard on you during my campaign. That money from the Clinton friend—I was very hard. I said a lot of tough things about your wife in the campaign.” 6park.com

“I know,” McCabe replied. “We heard what you said.” He told Trump that Jill was a dedicated doctor, that running for office had been another way for her to try to help her patients. He and their two teenage children had completely supported her decision.

“Oh, yeah, yeah. She’s great. Everybody I know says she’s great. You were right to support her. Everybody tells me she’s a terrific person.”

The next morning, while McCabe was meeting with his senior staff about the Russia investigation, the White House called—Trump was on the line. This was disturbing in itself. Presidents are not supposed to call FBI directors, except about matters of national security. To prevent the kind of political abuses uncovered by Watergate, Justice Department guidelines dating back to the mid-’70s dictate a narrow line of communication between law enforcement and the White House. Trump had repeatedly shown that he either didn’t know or didn’t care.

Read: Andrew McCabe couldn’t believe the things Trump said about Putin

The president was upset that McCabe had allowed Comey to fly back from Los Angeles on the FBI’s official plane after being fired. McCabe explained the decision, and Trump exploded: “That’s not right! I never approved that!” He didn’t want Comey allowed into headquarters—into any FBI building. Trump raged on. Then he said, “How is your wife?”

“She’s fine.”

“When she lost her election, that must have been very tough to lose. How did she handle losing? Is it tough to lose?” 6park.com

McCabe said that losing had been difficult but that Jill was back to taking care of children in the emergency room.

“Yeah, that must have been really tough,” the president told his new FBI director. “To lose. To be a loser.”

As McCabe held the phone, his aides saw his face go tight. Trump was forcing him into the humiliating position of not being able to stand up for his wife. It was a kind of Mafia move: asserting dominance, emotional blackmail.

“It elevates the pressure of this idea of loyalty,” McCabe told me recently. “If I can actually insult your wife and you still agree with me or go along with whatever it is I want you to do, then I have you. I have split the husband and the wife. He first tried to separate me from Comey—‘You didn’t agree with him, right?’ He tried to separate me from the institution—‘Everyone’s happy at the FBI, right?’ He boxes you into a corner to try to get you to accept and embrace whatever bullshit he’s selling, and if he can do that, then he knows you’re with him.”

McCabe would return to the conversation again and again, asking himself if he should have told Trump where to get off. But he had an organization in crisis to run. “I didn’t really need to get into a personal pissing contest with the president of the United States.”

Far from being the political conspirator of Trump’s dark imaginings, McCabe was out of his depth in an intensely political atmosphere. When Trump demanded to know whom he’d voted for in 2016, McCabe was so shocked that he could only answer vaguely: “I played it right down the middle.” The lame remark embarrassed McCabe, and he later clarified things with Trump: He was a lifelong Republican, but he hadn’t voted in 2016, because of the FBI investigations into the two candidates. This straightforward answer only deepened Trump’s suspicions.

But the professionalism that left McCabe exposed to Trump’s bullying served him as he took charge of the FBI amid the momentous events of that week. “Once Jim got fired, Andy’s focus and resolve were quite amazing,” James Baker, then the FBI general counsel, told me. McCabe had two urgent tasks. The first was to reassure the 37,000 employees now working under him that the organization would be all right. On May 11, in a televised Senate hearing, he was asked whether White House assertions of Comey’s unpopularity in the bureau were true. McCabe had prepared his answer. “I can tell you that I hold Director Comey in the absolute highest regard,” he said. “I can tell you also that Director Comey enjoyed broad support within the FBI and still does to this day.” He was saying to the country and his own people what he couldn’t say to Trump’s face. “The president is going to be out for blood and it’s going to be mine,” McCabe said.

The second task was to protect the Russia investigation. Comey’s firing, and the White House lies about the reason—that it was over the Clinton email case, when all the evidence pointed to the Russia investigation—raised the specter of obstruction of justice. On May 15, McCabe met with his top aides—Baker, Lisa Page, and two others—and concluded that they had to open an investigation into Trump himself. They had to find out whether the president had been working in concert with Russia and covering it up.

The case was under the direction of the deputy attorney general, Rod Rosenstein. McCabe doubted that Rosenstein, whose memo Trump had used to justify firing Comey, could be trusted to withstand White House pressure to shut down the investigation. He urged Rosenstein to appoint a special counsel to take over the case. Then it would be beyond the reach of the White House and the Justice Department. If Trump tried to kill it, the world would know. McCabe pressed Rosenstein several times, but Rosenstein kept putting him off.

On May 17, McCabe informed a small group of House and Senate leaders that the FBI was opening a counterintelligence investigation into Trump for possible conspiracy with Russia during the 2016 campaign, as well as a criminal investigation for obstruction of justice. Rosenstein then announced that he was appointing Robert Mueller to take over the case as special counsel.

That night McCabe was chauffeured in the unfamiliar silence of the director’s armored Suburban to his house in the Virginia exurbs beyond Dulles Airport. Jill was making dinner while their daughter did her homework at the kitchen island. McCabe took off his jacket, loosened his tie, and opened a beer. Ever since Comey’s firing he’d felt as though he were sprinting toward a goal—to make the Russia investigation secure and transparent. “We’ve done what we needed to do,” he said. “The president is going to be out for blood and it’s going to be mine.”

“You did your job,” Jill said. “That’s the important thing.”

In the coming months, when things grew dark for the McCabes, Jill would remind Andy of that evening together in the kitchen.

the tweets abruptly resumed on July 25: “Problem is that the acting head of the FBI & the person in charge of the Hillary investigation, Andrew McCabe, got $700,000 from H for wife!” By now Trump knew McCabe’s name, but Jill would always be the “wife.” The next day, more tweets: “Why didn’t A.G. Sessions replace Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe, a Comey friend who was in charge of Clinton investigation but got … big dollars ($700,000) for his wife’s political run from Hillary Clinton and her representatives. Drain the Swamp!”

The tweets mortified McCabe. He had no way of answering the false charge without calling more attention to it. He went into headquarters and made a weak joke about the day’s news and tried to keep himself and his organization focused on work while knowing that everyone he met with was thinking about the tweets. Baker, who also became a target of Trump’s tweets, described their effect to me. “It’s just a very disorienting, strange experience for a person like me, who doesn’t have much of a public profile,” he said. “You can’t help having a physiological reaction, like getting nervous, sweating. It’s frightening, and you don’t know what it’s going to mean, and suddenly people start talking about you, and you feel very exposed—and not in a positive way.”

Read: The cost of Trump’s attacks on the FBI

The purpose of Trump’s tweets was not just to punish McCabe for opening the investigation, but to taint the case. “He attacks people to make his misdeeds look like they were okay,” Jill said. “If Andrew was corrupt, then the investigation was corrupt and the investigation was wrong. So they needed to do everything they could to prove Andrew McCabe was corrupt and a liar.”

Three days after the tweets resumed, on July 28, McCabe was urgently summoned to the Justice Department. Lawyers from the Office of the Inspector General who were looking into the Clinton email investigation had found thousands of text messages between McCabe’s counsel, Lisa Page, and the bureau’s ace investigator, Peter Strzok. Both of them had been central to the Clinton and Russia cases; Strzok was now working for Mueller. During the campaign, Page and Strzok had exchanged scathing comments about Trump. They had also been having an extramarital affair. Page and Strzok were among McCabe’s closest colleagues; Page was his trusted friend. This was all news to him—terrible news.

The lawyers fired off questions about the texts. Because McCabe was a subject of the inspector general’s investigation of the Clinton case, he told the lawyers in advance that he wouldn’t answer questions about his involvement without his personal attorney present. In spite of this, their questions suddenly veered to the second Wall Street Journal article, with its suggestion that McCabe had been corrupted by Clinton. One of the lawyers wondered whether “CF” in a text from Page referred to the Clinton Foundation. “Do you happen to know?” he asked McCabe.

“I don’t know what she’s referring to.”

“Or perhaps a code name?”

“Not one that I recall,” McCabe said, “but this thing is, like, right in the middle of the allegations about me, and so I don’t really want to get into discussing this article with you. Because it just seems like we’re kind of crossing the strings a little bit there.”

“Was she ever authorized to speak to reporters in this time period?” a lawyer asked.

“Not that I’m aware of.”

This wasn’t true. McCabe himself had authorized Page to speak to the Journal reporter. But he had stopped paying attention to the lawyers’ questions, which weren’t supposed to have come up at all—he wanted to put an end to them. He had to think through how he was going to deal with this new emergency. The Page-Strzok texts were bound to leak, and they would be claimed by Trump and his partisans as proof that the FBI was a cesspool of bias and corruption. Page and Strzok would be personally destroyed. In New York City that day, Trump made his remark about Central American “animals,” and he urged law-enforcement officers to rough up suspected gang members. The bureau would have to formulate a response and reaffirm its code of integrity. And the McCabes were back in the president’s crosshairs.

McCabe had the sense that everything was falling apart. It’s not hard to imagine the state of mind that led him to say, “Not that I’m aware of.” He had done it before, on the other terrible day of that year, May 9, when a different internal investigation had blindsided him with the same question about the long-ago Journal leak, and McCabe had given the same inaccurate answer. A right-down-the-middle career official, his integrity under continued assault, might well make such a needless mistake.

That was a Friday. Over the weekend he realized that he had left the lawyers with a false impression. On Tuesday he called the inspector general’s office to correct it. That same week the Senate confirmed Christopher Wray as the new FBI director, and McCabe went back to being the deputy. After 21 years as an agent, he planned to retire as soon as he was eligible, in March 2018, when he turned 50, and go into the private sector. But it was already too late.

On December 19, testifying before a House committee, McCabe confirmed Comey’s account of Trump’s attempt to kill the Russia investigation. Two days later, before another House committee, he was asked how attacks on the FBI had affected him. “I’ll tell you, it has been enormously challenging,” McCabe said. He described how his wife—“a wonderful, brilliant, caring physician”—had run for office to help expand health insurance for poor people. “And having started with that noble intention, to have gone through what she and my children have experienced over the last year has been—it has been devastating.”

Two days before Christmas, Trump let fly a menacing tweet: “FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe is racing the clock to retire with full benefits. 90 days to go?!!!” No personnel issue was too small for the president’s attention if it concerned a bureaucrat he considered an enemy. Another tweet that same day and one on Christmas Eve repeated the old falsehoods about Jill’s campaign. She couldn’t stop blaming herself for all the trouble that had come to her family.

From December 2019: Yoni Appelbaum on how America ends

Just after the holidays, McCabe learned that his part of the inspector general’s report on the Clinton email investigation would be released separately. Instead of later in the spring, the McCabe piece would be finished in just a couple of months. In January 2018, Wray, the new director, forced McCabe out of the deputy’s job. Rather than accept a lower position, he went on leave in anticipation of his retirement in mid-March. At the end of February, the inspector general completed his 35-page report with its devastating conclusion: McCabe had shown “lack of candor” on four occasions in his statements about the Wall Street Journal leak. The Office of Professional Responsibility recommended that he be fired. To some in the Justice Department, this represented accountability for a senior official.

McCabe received the case file on March 9. FBI guidelines generally grant the subject 30 days to respond, but the Justice Department seemed determined to satisfy the White House and get ahead of McCabe’s retirement. He was given a week. On Thursday, March 15, he met with a department official and argued his case: He’d been blindsided by questions about an episode that he’d forgotten in the n0nstop turmoil of the following months, and when he realized that he’d made an inaccurate statement, he had come forward voluntarily to correct it. McCabe thought he made a solid argument, but he knew what was coming.

On Friday night, watching CNN, McCabe learned that he had been fired from the organization where he had worked for 21 years. He was 26 hours away from his 50th birthday.

An hour after the news broke, Trump broadcast his delight: “Andrew McCabe FIRED, a great day for the hard working men and women of the FBI—A great day for Democracy.” It was his eighth tweet about McCabe; there have been 33 since then, and counting. “There’s a lot of people out there who are unwilling to stand up and do the right thing, because they don’t want to be the next Andrew McCabe.”

“To be fired from the FBI and called a liar—I can’t even describe to you how sick that makes me to this day,” McCabe told me, nearly two years later. “It’s so wildly offensive and humiliating and just horrible. It bothers me as much today as it did on March 16, when I got fired. I’ve thought about it for thousands of hours, but it still doesn’t make it any easier to deal with.”

The extraordinary rush to get rid of McCabe ahead of his retirement, with the president baying for his scalp, appalled many lawyers both in and out of government. “To engineer the process that way is an unforgivable politicization of the department,” the legal expert Benjamin Wittes told me. McCabe lost most of his pension. He became unemployable, and “radioactive” among his former colleagues—almost no one at headquarters would have contact with him. Worst of all, the Justice Department referred the inspector general’s report to the U.S. attorney for Washington, D.C. A criminal indictment in such cases is almost unheard of, but the sword of the law hung over McCabe’s head for two years, an abnormally long time, while prosecutors hardly uttered a word. Last September, McCabe learned from media reports that a grand jury had been convened to vote on an indictment. He and Jill told their children that their father might be handcuffed, the house might be searched, he might even be jailed. The grand jury met, and the grand jury went home, and nothing happened. The silence implied that the jurors had found no grounds to indict. One of the prosecutors dropped off the case, unusual at such a crucial stage, and another left for the private sector, reportedly unhappy about political pressure. Still, the U.S. Attorney’s Office kept the case open until mid-February, when it was abruptly dropped.

McCabe discusses his situation with the oddly calm manner of the straight man in a Hitchcock movie who can’t quite fathom the nightmare in which he’s trapped. Jill, who is more demonstrative, compares the ordeal to an abusive relationship: Every time she feels like she can finally breathe a little, another blow lands. On any given night, a Fox News host can still be heard denouncing her husband. Just recently, a reporter for a right-wing TV network, One America News, announced on the White House lawn that McCabe had had an affair with Lisa Page. It was a lie, and the network was forced to retract it, but not before McCabe had to call his daughter at school and warn her that she would see the story on the internet.

McCabe has written a book, and he appears regularly on CNN, and he volunteers his time with the Innocence Project, working on the cases of wrongly convicted prisoners. Jill is getting an M.B.A. while continuing to do the overnight shift at the emergency room. But they’ve come to accept that they will never be entirely free.

Every member of the FBI leadership who investigated Trump has been forced out of government service, along with officials in the Justice Department, and subjected to a campaign of vilification. Even James Baker, who was never accused of wrongdoing, found himself too controversial to be hired in the private sector. But it is McCabe’s protracted agony that provides the most vivid warning of what might happen to other career officials if their professional duties ever collide with Trump’s personal interests. It struck fear in Erica Newland and her colleagues in the Office of Legal Counsel. It chilled officials farther afield, in the State Department. “There’s a lot of people out there,” Jill said, “who are unwilling to stand up and do the right thing, because they don’t want to be the next Andrew McCabe.”

4. Ends and Means

Nothing constrained Trump more than independent law enforcement. Nothing would strengthen him like the power to use it for his own benefit. “The authoritarian leader simply has to get control over the coercive apparatus of the state,” Susan Hennessey and Benjamin Wittes write in their new book, Unmaking the Presidency. “Without control of the Justice Department, the would-be tyrant’s tool kit is radically incomplete.”

When Trump nominated William Barr to replace Jeff Sessions as attorney general, the Washington legal establishment exhaled a collective sigh of relief. Barr had held the same job almost 30 years earlier, in the last 14 months of the first Bush presidency. He was now 68 and rich from years in the private sector. He had nothing to prove and nothing to gain. He was considered an “institutionalist”—quite conservative, an advocate of strong presidential power, but not an extremist. Because he was intimidatingly smart and bureaucratically skillful, he would protect the Justice Department from Trump’s maraudings far better than the intellectually inferior Sessions and his ill-qualified temporary replacement, Matthew Whitaker. Barr told a friend that he agreed to come back because the department was in chaos and needed a leader with a bulletproof reputation.

Before Barr’s confirmation hearings, Neal Katyal, a legal scholar who was acting solicitor general under Obama, warned a group of Democratic senators not to be fooled: Barr’s views were well outside mainstream conservatism. He could prove more dangerous than any of his predecessors. And the reasons for concern could be found by anyone who took the trouble to study Barr’s record, which was made of three durable, interwoven strands.

The first was his expansive view of presidential power, sometimes called the theory of the “unitary executive”—the idea that Article II of the Constitution gives the president sole and complete authority in the executive branch, with wide latitude to interpret laws and make war. When Barr became head of the Office of Legal Counsel under George H. W. Bush, in 1989, he wrote an influential memo listing 10 ways in which Congress had been trespassing on Article II, arguing, “Only by consistently and forcefully resisting such congressional incursions can executive branch prerogatives be preserved.” He created and chaired an interagency committee to fight document requests and assert executive privilege.

David Frum: Bill Barr sees the law as a tool of class warfare

One target of Barr’s displeasure was the Office of the Inspector General, created by Congress in 1978 as an independent watchdog in executive-branch agencies. “For a guy like Barr, this goes to the core of the unitary executive—that there’s this entity in there that reports to Congress,” says Jack Goldsmith, a Harvard law professor who served as head of the Office of Legal Counsel under George W. Bush. When Barr became attorney general in 1991, he made sure that the inspector general’s office in the Justice Department had as little power as possible to investigate misconduct.

Barr has even expressed skepticism about the guidelines, established after Watergate, that insulate the Justice Department from political interference by the White House. In a 2001 oral history Barr said, “I think it started picking up after Watergate, the idea that the Department of Justice has to be independent … My experience with the department is that the most political people in the Department of Justice are the career people, the least political are the political appointees.” In Barr’s view, political interference in law enforcement is almost a contradiction in terms. Since presidents (and their appointees) are subject to voters, they are better custodians of justice than the anonymous and unaccountable bureaucrats known as federal prosecutors and FBI investigators. Barr seemed unconcerned about what presidents might do between elections.

The Iran-Contra scandal that took place under Ronald Reagan shadowed Bush’s presidency in the form of an investigation conducted by the independent counsel Lawrence Walsh. Barr despised independent counsels as trespasses on the unitary executive. A month before Bush left office, Barr persuaded the president to issue full pardons of several Reagan-administration officials who had been found guilty in the scandal, in addition to one—former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger—who had been indicted and might have provided evidence against Bush himself. The appearance of a cover-up didn’t trouble Barr. But six years later, when the independent counsel Kenneth Starr was investigating President Bill Clinton for perjury and obstruction in a sex scandal, Barr, by then a corporate lawyer, criticized the Clinton White House for attacks on Starr that could impede the investigation and even intimidate jurors and witnesses.

Here is a glimpse of the second strand in Barr’s thinking: partisanship. Less conspicuous than the first, which sheathes it in constitutional principles, it never disappears. Barr is a persistent critic of independent counsels—except when they’re investigating a Democratic president. He’s a vocal defender of presidential authority—when a Republican is in the White House.

Quinta Jurecic and Benjamin Wittes: Imagine if a Democrat behaved like Bill Barr

This partisanship has to be understood in relation to the third enduring strand of Barr’s thinking: He is a Catholic—a very conservative one. John R. Dunne, who ran the Justice Department’s civil-rights division when Barr was attorney general under Bush, calls him “an authoritarian Catholic.” Dunne and his wife once had dinner at Barr’s house and came away with the impression of a traditional patriarch whom only the family dog disobeyed. Barr attended Columbia University at the height of the anti-war movement, and he drew a lesson from those years that shaped many other religious conservatives as well: The challenge to traditional values and authority in the 1960s sent the country into a long-term moral decline.

In 1992, as attorney general, Barr gave a speech at a right-wing Catholic conference in which he blamed “the long binge that began in the mid-1960s” for soaring rates of abortion, drug use, divorce, juvenile crime, venereal disease, and general immorality. “The secularists of today are clearly fanatics,” Barr said. He called for a return to “God’s law” as the basis for moral renewal. “There is a battle going on that will decide who we are as a people and what name this age will ultimately bear.” One of Barr’s speechwriters at the time was Pat Cipollone, who is now Trump’s White House counsel and served as one of his defenders during impeachment. In 1995, as a private citizen, Barr published the same argument, with the same military metaphors, as an essay in the journal then called The Catholic Lawyer. “We are locked in a historic struggle between two fundamentally different systems of values,” he wrote. “In a way, this is the end product of the Enlightenment.” The secularists’ main weapon in their war on religion, Barr continued, is the law. Traditionalists would have to fight back the same way.

What does this apocalyptic showdown have to do with Article II and the unitary executive? It raises the stakes of politics to eschatology. With nothing less than Christian civilization at stake, the faithful might well conclude that the ends justify the means. Barr and Trump are collaborating to destroy the independence of anything that could restrain

贴主:Leon21于2021_01_22 10:46:43编辑

Photo rendering by Patrick White

Photo rendering by Patrick White